Historical Reporting

Wheat Shipments

All values in Tons

Lewis-Clark Terminal

Average annual bushels at the Port of Lewiston

1994/1995/1996 = 18,700,000

2012/2013/2014 = 22,500,000

BreakBulk Cargo Tonnage

All values in Tons

Container Shipments

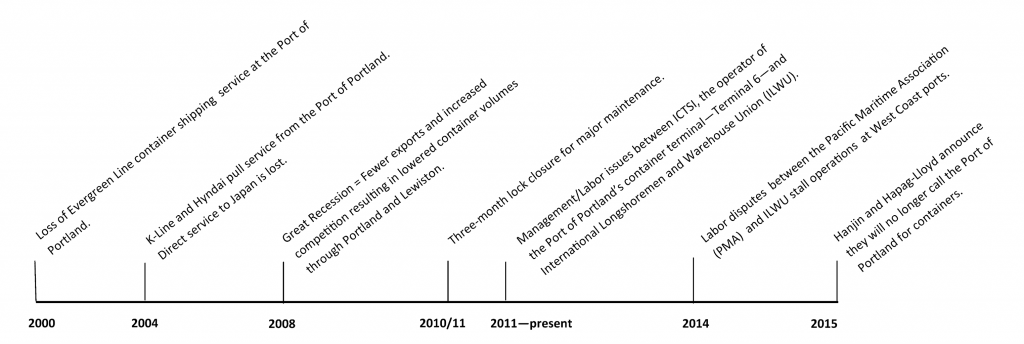

TIMELINE OF EVENTS CONTRIBUTING TO DECLINE IN CONTAINER SHIPPING

The Port of Lewiston’s decline in container shipments, as well as the overall decline in container shipments through the Port of Portland, does not correlate to a decline in export cargo from our region. Export cargo from eastern Washington and north central Idaho is strong. However, the decline in usage of the Columbia Snake River System for container on barge shipping can be contributed chronologically to:

2000: Loss of Evergreen Line container shipping service at the Port of Portland. On-going labor/management issues result in termination of steamship service.

2004: Reduction in service. Two of the Port of Portland’s transpacific containerized services (K-Line and Hyundai) left Portland in response to service issues and the relocation of a few frozen potato processing plants away from the river system. With this, the Port of Portland lost direct service to Japan, which greatly impacted the Ports of Pasco, Umatilla and Lewiston. At this time, approximately 40 percent of the Port of Lewiston’s container volume was exported to Japan.

2008: Great Recession. Fewer exports and increased competition for cargo resulted in lowered container volumes through Portland and Lewiston. Significant reduction in container volumes were documented at both East and West Coast ports.

2010/11: Three-month lock closure. The river system was closed to all upriver traffic for major maintenance projects and cargo was diverted to rail and roads. Efforts were made to incentivize shippers to return to the river system after the closure and volumes improved for 2012.

2011 to present: Issues develop between ICTSI, the operator of the Port of Portland’s container terminal – Terminal 6 – and International Longshoremen and Warehouse Union (ILWU). For example, ICTSI instituted a requirement of 100 minimum containers to work a barge, which was later elevated to 150 minimum. Costs for “dead time” and labor were also passed on to shippers and carriers in a somewhat unpredictable manner. Although barging containerized freight is significantly cheaper than trucking, some shippers began to favor alternative routes because they did not know exactly what the terminal charges in Portland would be and they were uncertain their container would make the intended ocean vessel due to management/labor issues.

2014: Labor disputes arise between the Pacific Maritime Association and ILWU. This stalled operations at West Coast ports until resolved in early 2015. After an agreement was reached between PMA and ILWU, issues between ICTSI and ILWU remained.

2015: Hanjin and Hapag-Lloyd announce they will no longer call the Port of Portland for containers. Low productivity and high costs cause Hanjin and Hapag-Lloyd to terminate service at the Port of Portland. The loss of service suspended all container on barge service on the Columbia-Snake River System.

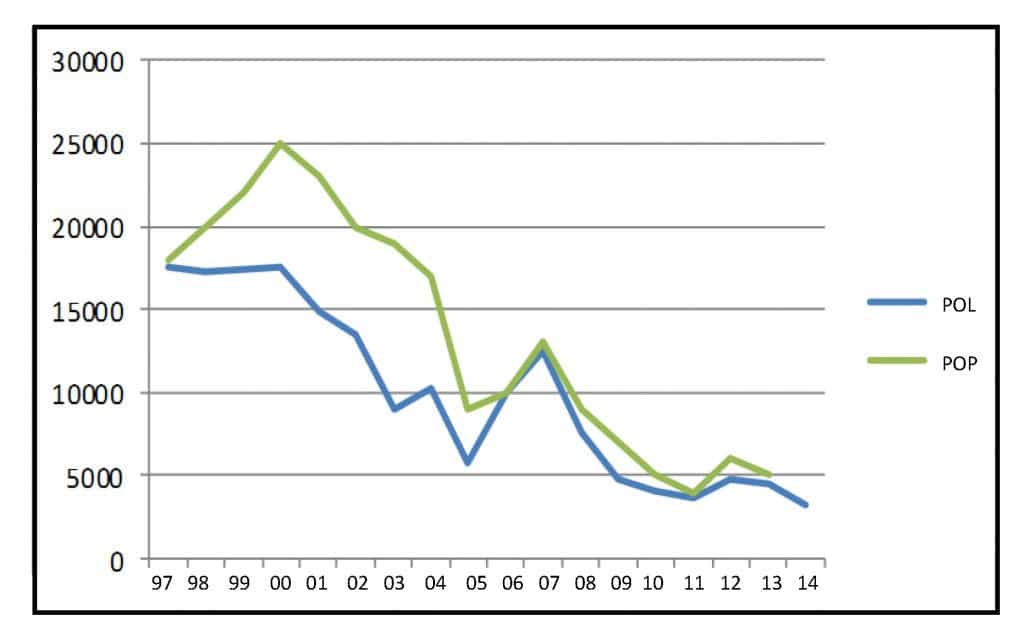

This chart compares POL outbound container shipments by us with the approximate amount of outbound containers barged into the port of Portland for export. this shows how shipping trends at the port of Portland compare to trends at the Port of Lewiston. it also illustrates the role the Port of Lewiston has played in the total number of containers shipping by barge to Portland for export overseas.